In February of this year (2025), Microsoft discovered cyberattacks being launched by a group they call Storm-2372, which is suspected to be associated with Russian interests. The attacks have been ongoing since August 2024 and have targeted governments, NGOs, and a wide range of industries across multiple regions. These attacks use a phishing technique called “device code phishing,” in which the user is brought to a legitimate Microsoft website to log in—but their access and refresh tokens are still harvested.

How it Works

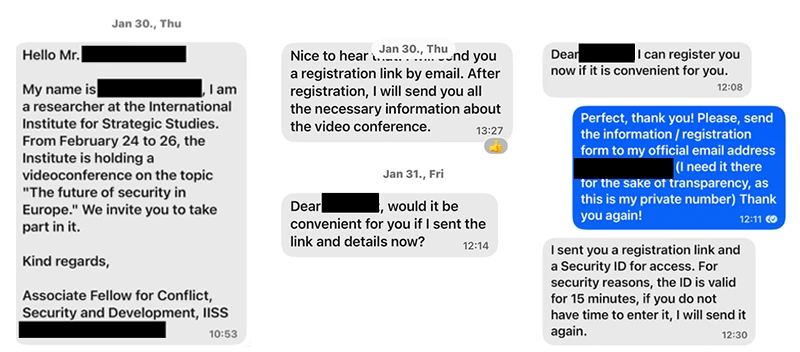

Like a typical phishing operation, the attacker begins by building rapport with a specific individual, often pretending to be an important person in their field. After exchanging a few messages, they invite the target to a Microsoft Teams meeting.

The link sent is completely legitimate, and the user logs in as usual. The twist is that the user is unknowingly authenticating a malicious application through Microsoft’s legitimate OAuth 2.0 device code flow. We’re so used to allowing apps to access our data that we may unconsciously click “Allow” without reading the permissions. However, in this case, the user is authorizing the threat actor’s app, granting them access to the account—such as reading emails, accessing files, or impersonating the user—so long as the refresh token remains valid.

Below is a diagram representing how the operation works.

The Danger

What makes this form of initial access clever is that there are none of the usual indicators we look for in phishing attacks. The login page really does say https://microsoft.com/..., and the Teams meeting invite looks authentic.

Even if you’re a security-conscious user who uses a password manager with strong passwords and has multi-factor authentication (MFA) enabled, those defenses won’t protect you here. In some ways, the access token that the attacker obtains is even more powerful than a password. It bypasses both the password and the MFA step, while still granting the same privileges that you have.

Revoking access is relatively simple, but most users have never needed to remove app permissions from their accounts—let alone monitor token activity.

Once an account is compromised, the attacker can move laterally within the network and easily pose as a legitimate user to phish others inside the organization.